Stu Hart

| Stu Hart OC | |

|---|---|

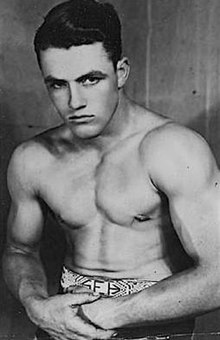

Hart, aged approximately 18, with an amateur wrestling championship belt.[a] | |

| Birth name | Stewart Edward Hart |

| Born | May 3, 1915[2] Saskatoon,[3] Saskatchewan, Canada |

| Died | October 16, 2003 (aged 88) Calgary, Alberta, Canada |

| Cause of death | Stroke |

| Spouse(s) |

Helen Louise Smith

(m. 1947; died 2001) |

| Children | 12, including Smith, Bruce, Keith, Dean, Bret, Ross, Diana, and Owen |

| Relatives | Donald Stewart (grandfather) Harry Smith (father-in-law) |

| Family | Hart |

| Professional wrestling career | |

| Billed height | 5 ft 11 in (180 cm)[iii] |

| Billed weight | 230 lb (104 kg)[iii] |

| Billed from | Calgary, Alberta, Canada |

| Trained by | Jack Taylor[b] Toots Mondt[c] |

| Debut | 1943[6] |

| Retired | 1986[7] |

| Military service | |

| Buried | Eden Brook Memorial Gardens |

| Allegiance | Canada |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1942–1946 |

| Battles / wars | World War II |

Stewart Edward Hart OC (May 3, 1915 – October 16, 2003) was a Canadian amateur and professional wrestler, wrestling booker, promoter, and coach. He is best known for founding and handling Stampede Wrestling, a professional wrestling promotion based in Calgary, Alberta, teaching many individuals at its associated wrestling school "The Dungeon" and establishing a professional wrestling dynasty consisting of his relatives and close trainees. As the patriarch of the Hart wrestling family, Hart is the ancestor of many wrestlers, most notably being the father of Bret and Owen Hart as well as the grandfather of Natalya Neidhart, Teddy Hart and David Hart Smith.

Hart was born to a poor Saskatchewan family but became a successful amateur wrestler during the 1930s and early 1940s, holding many national championships, as well as engaging in many other sports. He began wrestling for show in 1943 with the Royal Canadian Navy while serving in World War II as he could not go to the 1940 Summer Olympics due to the war. After leaving the service he travelled to America and debuted professionally for the New York wrestling territory[d] in 1946. Hart was considered very handsome and a good in-ring performer, focusing on a submission-like and technical style of wrestling, but despite this and being popular in general he was not given a major spotlight, and soon after marrying Helen Smith, whom he met in New York City, he created his own promotion in Edmonton, Alberta, which would be known as Stampede Wrestling[e] and took over the surrounding wrestling territory which covered most of western Canada and the US state of Montana. The territory would go on to become known as the Stampede territory thenceforth. In 1949, Stu and Helen moved to Great Falls, Montana. Hart's promotion featured a large variety of outside stars from the wrestling industry as well as homegrown talent for whom he booked storylines. Beginning from the 1950s Hart helped train a large number of people for his company and gained a reputation as one of the best teachers in the wrestling business. In October 1951, Stu and Helen moved to Calgary, Alberta, into what would become the famous Hart House.

Hart remained an active full-time wrestler until the 1960s when he entered semi-in-ring retirement, thereafter he would focus mostly on promoting, booking and teaching, as well as raising his twelve children with Helen while still appearing in the ring sporadically until the 1980s. Throughout his career, Hart almost exclusively portrayed a heroic character, a so-called "babyface" role and only held one professional title, the NWA Northwest Tag Team Championship. After selling his territory to Titan Sports, Inc. in 1984, Hart would make several appearances on WWF television and Pay-Per-View with his wife, often involved in storylines surrounding his sons Bret and Owen and several of his sons-in-law who were signed to the company. He continued to teach wrestling at his home in Calgary until the 1990s when he suffered a severe leg injury and had to stop engaging excessively with students, leaving most of the work for his sons Bruce and Keith. He died at age 88 in October 2003 after suffering from multiple medical issues.

Hart is regarded by many, including major wrestling historian and sports journalist Dave Meltzer, as one of the most influential and important figures in professional wrestling history and an icon of the artform. His greatest contribution to the art was as a promoter and trainer. Along with Bret and Owen, Hart's trainees included future world champions Fritz Von Erich, Superstar Billy Graham, Chris Jericho, Edge, Christian, Mark Henry, Chris Benoit, and Jushin Thunder Liger. Hart was a member of the inaugural Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame class in 1996 and was inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame in 2010 by his son Bret. Hart was also well known for his involvement in over thirty charities, for which he was named a Member of the Order of Canada,[Quote 2] the second highest honour for merit which can be given in Canada and the highest civilian honour.

Early life

[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Professional wrestling |

|---|

|

Hart was born in Saskatoon in 1915[iii] to Edward and Elizabeth Stewart Hart. He was mainly of Ulster Scot descent from his father's side but also had Scottish and English ancestry from his mother's side of the family.[9][10]

His childhood was impoverished; as a boy, Stu Hart lived in a tent with his family on the prairie in Alberta, living off the land, milking cows[11] and wild game that Stu took down with his slingshot.[12] As a child Hart and his sisters were often mistreated at school by both fellow students and teachers since it was well known that they were from such a poor family. Hart was also berated and treated with disdain for being lefthanded, something seen as deviant at the time. Like most lefthanded children at the time, he was forced to work with his right, and as a result he became ambidextrous.[13] In 1928, his father was arrested for failure to pay back taxes, while the Salvation Army sent Stu, his mother, and two sisters, Sylvester and Edrie to live in Edmonton.[iv] Due to his destitute childhood and youth Hart did not experience a dramatic shift in life quality or mentality during the Great Depression which affected most others around him in Edmonton.[14]

Amateur wrestling

[edit]Hart was trained in catch wrestling in his youth by other boys. Speaking of it, Stu said that his "head would be blue by the time they let go of him". Stu taught this 'shoot style' to all who trained under him in the 1980s and 1990s with the thought that teaching his students real submission moves would make their professional wrestling style sharper. During his time in Edmonton with his mother and sisters Hart began finding an interest in sports with wrestling and football being his favourites.[v] He started weightlifting and training for wrestling when he was fourteen years old and quickly built a strong neck and impressive arms.[15] He began attending amateur wrestling classes when he joined the YMCA in Edmonton in 1929 and soon became a talented grappler. By the age of fifteen Hart won the Edmonton City Championship in the middleweight class and the Alberta Provincial championship later that same year. Hart continued to train and improve his abilities and by 1937 he was the Dominion welterweight champion, also in 1937 he won a gold medal in the welterweight class from the Amateur Athletic Union of Canada. Hart qualified for the 1938 British Empire Games in Australia but was unable to go due to economic reasons,[16] mainly the lack of funding from the Canadian government, a leftover from the depression.[15] During the mid-1930s Hart also coached wrestling at the University of Alberta.[vi][17][vii]

His amateur career peaked in May 1940 when Hart won the Dominion Amateur Wrestling Championship in the light heavyweight category.[18] Hart qualified and would have competed at the Summer Olympics in Helsinki in 1940 but could not due to it being cancelled because of the outbreak of World War II, which was a terrible blow to Hart personally, as it had been his dream to compete at the Olympics from a very young age.[16]

Other sport ventures and military service

[edit]While Hart was mainly a lover of submission wrestling he was also an outstanding all-around athlete[viii] who played virtually every sport available,[11] excelling at football, baseball and fastball notably. Hart played professionally for the Edmonton Eskimos from 1937 to 1939 as a center and was considered a standout performer at the time.[16] Hart had initially been slated for the 1941 season as well but had to decline due to other commitments which prevented him from joining at that time.[ix][x] He coached a women's fastball team in Edmonton during the late 1930s as well as being the captain of a popular baseball team called Hart's All Stars.[19] The players of Hart's All Stars consisted of sheet-metal workers from Edmonton whom he trained.

On Christmas Eve 1941 Hart was almost killed in a bicycle accident which broke both his elbows and thumbs and hurt his back severely. The injuries risked ending Hart's athletic career. The accident happened while he was on the way to be with his father Edward to celebrate Christmas with the family when a fire truck drove behind him and forced Hart to swerve to the side where he was hit by another car which propelled him thirty feet forward on the road and scraped off a large portion of his skin in the process. He spent several months at the Royal Alexandra Hospital in Edmonton recovering. In the spring, still hospitalized, Hart was visited by Al Oeming, a young neighbour who had been drafted into the Royal Canadian Navy for World War II and after being released from the hospital Hart decided to enlist. Hart enlisted in the Navy and was appointed to the position of Director of Athletics.[17] In early 1943, Hart was put in for a transfer from the Nonsuch in Edmonton to regular service in Cornwallis, Nova Scotia. Physically, he had fully recovered from his injuries and had hoped to see genuine sea duty afterward, but the Navy appeared to be more interested in him as an athletic director than as a regular enlisted seaman. By later 1943 the Navy had him wrestling mostly to amuse the other servicemen, instead of purely competitively. He performed regularly before thousands of other enlisted men in drill halls.[6] Several of the men he worked with would end up being employed by Hart when he became a promoter later in life.[6]

Hart spent much of his free time during World War II performing and organizing different sports events to raise funds to the war effort.[xi] As an active sailor and director of athletics Hart was the leader of all the sports teams available and a member of them as well, most notably the fastball team and the wrestling team. Hart originally wanted to leave the Navy when the war was over but the organization considered him to be a great asset both as a trainer as well as a showpiece, persuading him to stay. He would attempt to ask to be let go several times later but was told to stay again. Eventually, Hart was given his discharge from the Navy in early 1946.[20]

Professional wrestling career

[edit]New York territory (1946–1947)

[edit]It was during his time in the Navy that Stu was introduced to professional wrestling.[xi] Around this time Hart and Al Oeming, a future wrestler, nature conservationist, and fellow sailor, became closer as friends. Oeming later would help him handle his own promotion.[xii][21]

After recovering from a car accident, Stu competed in various exhibition matches to entertain the troops. In 1946, while receiving training from Toots Mondt, Hart debuted in New York City. Early on, Hart experienced harsh treatment from his fellow wrestlers in the ring and during training, being considered a "pretty boy" at first by his peers and older wrestlers; described as "tall, dark and handsome, with a build that would put movie idols to shame" he was immediately a favourite with the female fans.[22][20] Hart would often be swarmed by women and covered with kisses as he made his way to the ring.[20][22] The roughing up of younger performers by veteran workers was common at the time in the industry but Hart adapted to it rather quickly and would retaliate with the same treatment, utilizing his catch wrestling experience to his advantage.[20] While never given the opportunity to be champion Hart did partake in several high-profile matches with the likes of Lou Thesz and Frank Sexton. He also developed a reputation as a legitimate athlete and "tough-guy" in the business.[iii] Hart was a frequent tag team wrestler together with Lord James Blears.[xiii][xiv] Blears and Hart lived together for six months with another wrestler named Sandor Kovacs whom Hart already knew from the Navy.[23] They used to frequent the beaches at Long Beach in New York on their free time and it was on the beach that Hart first met his wife Helen Smith and her family.[xi] Hart had quickly become a rising star in the area but chose to leave together with his newly engaged fiancée only about a year and a half after debuting.[5][24][22]

National Wrestling Alliance (1947–1984)

[edit]

By 1947, Hart was working for Jerry Meeker and Larry Tillman in Montana as both a wrestler and a booker.[25][26] In late 1947 he travelled to wrestle in San Antonio briefly.[xv] In September 1948, Hart established Klondike Wrestling[27] in Edmonton, the promotion joined the NWA in 1948.[Quote 1] In 1949, Hart was involved in a storyline with the "heel" Lord Albert Mills, they were scheduled to have a two out of three main event match at the Billings Sports arena on Monday December 19, the match was a followup to another one the previous week when Mills had gotten the win through nefarious means. Hart was portrayed as having been caught off guard the Monday before when it happened.[xvi] Hart was a perpetual "face" during his in-ring career, including during his time with the NWA,[xvii] and was a noted draw for women in the areas he wrestled.[xviii][xix] In 1950, Hart wrestled for the NWA associated Alex Turk Promotions in Winnipeg. The first match was against Verne Gagne on June 29 at the Civic Auditorium, the match resulted in a draw. He also wrestled in a match against Matt Murphy in the Civic Auditorium on November 9, which he was booked to win. In 1951, Hart purchased a mansion in Patterson Heights, Calgary, The Hart House which is now considered a heritage site. Its basement, later known as the Dungeon, provided training grounds for his wrestling pupils.[28] Later that year Hart headlined an event in Wisconsin, again together with Verne Gagne.[xx] Hart was still favoured by women at this time even against a bigger star like Gagne.[xxi]

Big Time Wrestling and Wildcat Wrestling (1952–1967)

[edit]In 1952, Hart bought up Tillman's territory in Alberta and merged his own promotion with it into Big Time Wrestling.[8] The promotion would later change name to Wildcat Wrestling and lastly morph into Stampede Wrestling many years later.[Quote 1] The televised version of Hart's wrestling shows were one of Canada's longest-running television programs, lasting over 30 years and remained one of Calgary's most popular sports programs, eventually airing in over 50 countries worldwide.[xxii]

Stampede Wrestling (1967–1986)

[edit]Hart's Stampede Wrestling was responsible for developing many wrestlers who would later become very successful in other promotions and territories, mainly in the WWF.[29][7][30] Hart would generally close the promotion down during summers and open it up again during the winter when the other territories were closed.[31][32] Hart had on occasions wrestled animals such as tigers and grizzly bears as part of promotional efforts for the company as well as charity.[xxiii][xxiv][xxv] Later in life Hart would often let his sons Bruce and Keith handle the booking of the promotion.[33]

On July 25, 1986, he wrestled his last match in a tag team match with his son, Keith defeating Honky Tonk Wayne and J.R. Foley at a Stampede Wrestling event in Calgary.[xxvi]

Post-retirement appearances (1991–2003)

[edit]Hart made several appearances on WWE television in the 1990s and early 2000s. The majority of those appearances involved his sons, Bret and Owen Hart. A recurring staple of these appearances in the 1990s was that Stu and Helen would be verbally attacked by several of the commentators, mostly by Bobby Heenan and Jerry Lawler, the latter of whom was in a long-running feud with Bret during this point in time.[34][35][36] At the 1993 Pay-Per-View event Survivor Series, Stu had a planned physical interaction outside of the ring with Shawn Michaels. Michaels was involved in a match with Stu's sons, Bruce, Keith, Bret and Owen Hart. Michaels played the part of the antagonist, and when failing to succeed in winning the match, Michaels' character then attacked Stu who responded by pretending to knock him out with an elbow smash.[citation needed] Michaels later stated that he was happy to take the hit as he considered it an honour.[37]

Hart also appeared in WCW at the Slamboree 1993: A Legends' Reunion event.[xxvii][xxviii]

As a trainer

[edit]Hart trained the vast majority of his trainees in the basement of the Hart mansion, known as The Dungeon. Hart used the location from the time that he bought it in October 1951 until the late 1990s. All eight of his sons and many others such as Junkyard Dog, Jushin Liger,[xxix] Superstar Billy Graham and The British Bulldog were educated there.[xxx][28]

Hart's training technique, called "stretching" consisted of Hart putting his trainees in painful submission holds and holding on for a substantial time to improve their pain endurance to prepare them for the life of professional wrestling.[2][xxxi][38] Hart's technique was well known and he would let anyone who wished to let him apply one of his holds do so if they came to his home. Hart's son Bret once spoke about a well-known case where he stretched a priest, stating that his father wasn't prejudiced, since "he stretched a rabbi once too."[39] Some of Hart's former students, including his son Bret, have mentioned that his stretching would sometimes result in broken blood vessels in the eyes,[40][41][2][42] something which others have attempted to learn from his father.[43]

Hart was said to have had a special liking for training football players and bodybuilders since he enjoyed testing their strength.[44] Some have described his training as torture[45] and have accused Hart of being a sadist who enjoyed inflicting pain on people and was more interested in doing so than teach them professional wrestling.[44][46][47][48][49][xxxii][50][51][52][53] Many who were close to Hart in his life have denied these claims.[xxxii][54][xxxiii] Stu's seventh son Ross has said that his father was always generous and compassionate with his children and others in person but added that he was different when training people, believing that there was no easy way to teach wrestling.[2] His daughter-in-law Martha has expressed in her book that she felt sure that Hart was well aware of his students' limits and never meant to actually harm any of them, stating that he was always careful not to apply too much pressure on any of his holds and intended more to scare them than maim them. Although she recalled several times when she thought she would pass out from the pain of the holds he had put on her, which he had meant as a playful gesture.[11] She added that it was fair to say that he had never seriously hurt anyone physically, albeit he may have inadvertently done so mentally.[55] Despite this, she also disclosed that her husband Owen had long been scared of his father during childhood due to his fearsome reputation and hearing his brothers as well as other trainees' screams from the family's basement where Hart's training hall was located. This fear lingered into Owen's adolescence but ceased when he became an adult.[45] Owen himself revealed in the 1998 documentary Hitman Hart: Wrestling with Shadows that he was often intimidated by his father but respected him and that that kept him from misbehaving. In the same documentary his third son Keith explained that many may have believed his father to be a psychopath at first glance but that you had to know him intimately to understand that he wasn't anything like that beneath the surface. Wrestling manager Jim Cornette has theorized that his cruel upbringing and tough early development may have played a part in the seemingly contradictory behaviour from Hart, as both a dedicated family man and apparently sadistic tormentor of his students.[xxxiv]

Wrestlers trained

[edit]- Abdullah the Butcher[56]

- Allen Coage[57]

- Archie Gouldie[56]

- Ben Bassarab[xxxv]

- Billy Jack Haynes[xxxvi]

- Dean Hart

- Smith Hart

- Ross Hart

- Wayne Hart[xxxvii]

- Bret Hart[58][f]

- Keith Hart[xxxvii]

- Bruce Hart

- Owen Hart[xxxvii]

- Brian Pillman

- Chris Benoit[xxxix]

- Chris Jericho[xl]

- Yvon Durelle

- Christian[xxxvii]

- Jesse Ventura[xli]

- Davey Boy Smith

- David Hart Smith

- Tyler Mane[xlii]

- Dynamite Kid

- Edge[xxxvii]

- Eduardo Miguel Perez

- Fritz Von Erich[60]

- Gama Singh

- Gene Anderson

- George Scott

- Gorilla Monsoon[61]

- Greg Valentine

- The Honky Tonk Man

- Jake Roberts

- Jim Neidhart

- Jos LeDuc

- Junkyard Dog

- Jushin Thunder Liger[xliii]

- Justin Credible

- Ken Shamrock

- Klondike Bill

- Lance Storm[xli]

- Larry Cameron

- Luther Lindsay[62]

- Hiro Hase[63]

- Mark Henry

- Masahiro Chono

- Michael Majalahti

- Natalya Neidhart

- Nikolai Volkoff[xliv]

- Paul LeDuc

- Reggie Parks

- Ricky Fuji[xlv]

- Roddy Piper[64][65]

- Sandy Scott

- Shinya Hashimoto

- Steve Blackman

- Superstar Billy Graham

- Tyson Kidd

- Tom Magee

- Ruffy Silverstein

- Al Oeming

- Outback Jack

Personal life

[edit]Hart was close friends with fellow wrestler Luther Jacob Goodall, better known by the name Luther Lindsay. Goodall was one of the few men who bested him in the infamous "Dungeon" and Hart reportedly carried a picture of him in his wallet until his passing in 2003. Goodall's death in 1972 affected Hart tremendously. Hart's son Keith described them as being as close as brothers.[66] Hart was also a good friend of wrestling promoter Jack Pfefer, whom he asked to be the godfather of his son Ross,[67] as well as Calgary Mayor Rod Sykes[15] and ice hockey player Brian Conacher.[68] All of the wrestling belts that Hart used for his promotions were handmade by himself. Making championship belts was one of Hart's many domestic skills.[1]

Hart allegedly wrote the foreword to the controversial book Under the Mat[69] which was written by his youngest daughter, Diana Hart. His son Bret has questioned the legitimacy of it, and has stated that if Hart did write the foreword, his daughter probably did not let him read the book beforehand.[70][xlvi]

Family

[edit]Hart married a New Yorker, Helen Smith (born February 16, 1924 – died November 4, 2001), the daughter of Olympic marathon runner Harry Smith on December 31, 1947.[xlvii] They were introduced through each other by Paul Boesch.[xlviii] Stu and Helen were married for over 53 years until Helen's death at the age of 77.

Stu and Helen raised their twelve children in the Hart mansion, Smith, Bruce, Keith, Wayne, Dean, Ellie, Georgia, Bret, Alison, Ross, Diana and Owen. Hart was a non-denominational Christian, however, he had all his children baptized by a local Catholic priest.[36] The couple have around thirty-six biological grandchildren and several great-grandchildren, three of whom, his oldest grandson Teddy Annis's son Bradley and his oldest granddaughter Tobi McIvor's two oldest daughters Amanda and Jessica, were born during Hart's lifetime. Tom and Michelle Billington's three children, Bronwyne, Marek and Amaris are also often included in the list of his grandchildren, therefore Bronwyne's daughter Miami is also often referred to as one of his great-grandchildren.[71] Many of his grandchildren went on to become wrestlers or were otherwise involved in wrestling.[72]

In 1949, Hart and his wife Helen who was pregnant with their second child, Bruce were in a car accident on their way home from a wrestling match, Hart was unscathed, although he did break the car's steering wheel on impact, however his wife Helen suffered several injuries and had to be held in a hospital for a long time, leading them to leaving their oldest child, Smith, with Helen's parents Elizabeth and Harry Smith for two years.[73][74][xlix]

According to his son Ross, Hart was severely affected and badly aged by being bereaved of his youngest son Owen in 1999 and by becoming a widower in 2001.[75]

Philanthropy

[edit]Because of his extensive work as a coach and mentor to many young athletes as well as over thirty years of charitable work in his hometown, Stu Hart was appointed a Member of the Order of Canada on November 15, 2000.[76] He was honoured with an investiture on May 31, 2001, in Ottawa.[77][viii][l][li][Quote 2]

Death

[edit]In May 2003, Hart had a life-threatening bout of pneumonia, which saw him hospitalized at Rockyview General Hospital, although Hart recovered later that month and returned to his residence at the Hart House.[78] On October 3, 2003, Hart was readmitted to Rockyview General Hospital as a result of an elbow infection at which point he then developed pneumonia again.[lii][liii][liv][lv] He also suffered from ailments associated with diabetes and arthritis. After a brief improvement in his health for a few days from October 11, he suffered a stroke on October 15, and died the following day. He was 88 years old.[79]

Hart's funeral service was attended by approximately 1,000 people. He was cremated and his ashes were later interred at Eden Brook Memorial Gardens in a plot with his wife Helen, who had died almost two years earlier in November 2001.[lvi][lvii]

Legacy

[edit]Hart is regarded by many as one of the most important and respected[80] people in the history of professional wrestling,[68][xli][81][lviii][lix][82][lx] and an icon of the art.[lxi]

Sports journalist and wrestling historian Dave Meltzer described Hart's importance to the art of professional wrestling as indispensable[75] since his booking decisions and training of several key individuals affected the industry in significant ways. Meltzer describes people like Hulk Hogan and Jesse Ventura as people who were spawned by Harts actions and cites the Dynamite Kid, Junkyard Dog and Billy Robinson as some who would probably not have had the careers they did if not for Hart. He also mentions Chris Benoit and Brian Pillman as individuals who would most certainly never even have become wrestlers were it not for Hart.[83] Meltzer characterized Hart as the biggest territorial star in wrestling history to never win a major championship.[84] Former wrestling promoter and owner of the St. Louis Wrestling Club Larry Matysik described Hart as a Canadian icon.[85]

Hart had a noticeable accent which included a very raspy voice[15] and unique way of speaking which he was well known for. According to the Wrestling Observer Newsletter, Hart is the most imitated man in professional wrestling,[86] with practically everyone in the industry having tried a Stu Hart impersonation.[4][lxii][lxiii]

WWE chairman Vince McMahon has lauded Hart as a trailblazer for the wrestling industry.[lxiv] On March 27, 2010, Hart was posthumously inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame.[lxv]

In the Hart Legacy Wrestling promotion, controlled by Hart's relatives and their associates, there is a Stu Hart Heritage Title.[lxvi][lxvii]

There is an annual juvenile amateur wrestling tournament named after Hart called the Stu Hart Tournament of Champions held in Canada.[lxviii][lxix][lxx][lxxi][lxxii][lxxiii][lxxiv][lxxv][lxxvi][lxxvii]

In Saskatoon's Blairmore Suburban Centre there is a road named Hart Road, in Stu Hart's honour.[lxxviii]

In 2005 a documentary directed by Blake Norton, Surviving the Dungeon: The Legacy of Stu Hart, was released.[lxxix][lxxx][lxxxi][lxxxii][lxxxiii][lxxxiv][lxxxv][lxxxvi]

As of 2005 Hart is part of a permanent exhibit at the Glenbow Museum.[lxxxvii] A scissored armbar wrestling hold is sometimes referred as a "Stu-Lock" in Hart's honour.[lxxxviii]

Championships and accomplishments

[edit]Amateur wrestling

[edit]- City, Edmonton

- Edmonton City Middleweight Championship (1930)[16]

- Provincial, Alberta

- Alberta Provincial Championship (1930)[16]

- National, Canada

- Dominion Amateur Wrestling

- Amateur Athletic Union of Canada

- Welterweight Championship (1937)[18]

- Alberta Sports Hall of Fame

- National Wrestling Hall of Fame

- Class of 2008[xc]

Professional wrestling

[edit]- Canadian Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame

- Class of 1980[16]

- Canadian Pro-Wrestling Hall of Fame

- Class of 2021[89]

- Cauliflower Alley Club

- George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame

- Class of 2008[xcii]

- National Wrestling Alliance

- NWA Northwest Tag Team Championship (2 times) – with Pat Meehan and Luigi Macera[xciii]

- Pro Wrestling This Week

- Wrestler of the Week (August 1, 1987)[xciv]

- Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame

- Stampede Wrestling

- Stampede Wrestling Hall of Fame (Class of 1995)[xcviii][xcix]

- World Wrestling Entertainment

- World Championship Wrestling

- Wrestling Observer Newsletter

- Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame (Class of 1996)[c][xiii]

- Canadian Wrestling Hall of Fame

- Prairie Wrestling Alliance

Luchas de Apuestas record

[edit]| Winner (wager) | Loser (wager) | Location | Event | Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stu Hart (hair) | Towering Inferno (mask) | Calgary, Alberta | Stampede show | February 6, 1976 | [civ] |

Accolades and recognitions

[edit]Honours and decorations

[edit]

| Ribbon | Description | Notes |

| Order of Canada (CM) |

Awards and nominations

[edit]- Western Legacy Awards (2012)[cvi]

- Calgary Awards (Signature Award, 1999)[cvii]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The belt Hart wears in the picture features his initials SEH.[1]

- ^ Mainly amateur wrestling.[4]

- ^ Mainly professional wrestling.[5]

- ^ Said territory later morphed into the Capitol Wrestling Corporation (CWC), World Wide Wrestling Federation (WWWF), World Wrestling Federation (WWF) and the latest World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE)

- ^ The original company founded in 1948 was named Klondike Wrestling, which would later be merged with another company Hart bought and bear the name of Big Time Wrestling and Wildcat Wrestling before becoming Stampede. See full quote:[Quote 1]

- ^ Stu mainly trained Bret in amateur wrestling.[59][xxxviii]

- ^ Hart was inducted mainly for his charitable work, his impact in the professional wrestling industry and for contributing to the Calgary community by being a mentor and role model to many athletes, both inside and outside of the wrestling industry. See full quote:[Quote 2]

- Quotations

- ^ a b c David Taras and Christopher Waddell state:

That same year [1948], the legendary Stu Hart founded Klondike Wrestling which he operated out of Edmonton. In 1952, through a series deals with [Larry] Tillman and [Jerry] Meeker, Hart acquired control of the Calgary promotion and thus became the promoter for the entire territory, which now operated under the name Big Time Wrestling (later Wildcat Wrestling and Stampede Wrestling).

- How Canadians Communicate V: Sports (2016), Athabasca University Press; ISBN 978-1-77199-007-3.[8]

- ^ a b c Hart's citation reads;

As patriarch of Canada's first family of professional wrestling, he has made an important contribution to the sport for more than five decades. Founder of Stampede Wrestling and an icon of the golden era of wrestling, he has been coach and mentor to countless young athletes, imparting the highest standards of athleticism and personal conduct. A generous supporter of community life in Calgary, he is a loyal benefactor to more than thirty charitable and civic organizations including the Shriners' Hospital for Crippled Children and the Alberta Firefighters Toy Fund.[cv]

References

[edit]- ^ "Mavericks: Helen Hart". Glenbow.org. Glenbow Museum. Archived from the original on August 2, 2019. Retrieved April 10, 2016.

- ^ Gallipoli, Thomas M. (February 22, 2008). "SPECIALIST: List of Deceased Wrestlers for 2001: Johnny Valentine, Terry Gordy, Chris Adams, Bertha Faye, Helen Hart". Pro Wrestling Torch. Retrieved April 14, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Stu Hart's Hall of Fame profile". WWE.com. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

- ^ Kaufmann, Bill (October 17, 2003). "Stu Hart leaves lasting legacy". Slam! Wrestling. Canadian Online Explorer. Archived from the original on August 18, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

He will be remembered as generous friend, tough trainer, loving husband and dad

- ^ "Who is Stu Hart?". Glenbow.org. Glenbow Museum. Archived from the original on August 2, 2019. Retrieved April 10, 2016.

- ^ "Wrestling Bibliography Abstracts". ashfm.ca. Alberta Sports History Library. Archived from the original on February 2, 2016.

- ^ Oliver, Greg (December 6, 1997). "The Stu Hart Interview: Part 2". Slam! Wrestling. Canadian Online Explorer. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Wrestling patriarch Stu Hart dies". CBC News. October 17, 2003. Archived from the original on September 20, 2014.

- ^ "The Football Team that History Forgot: 1941 Edmonton Eskimos - Canadian Football Research Society". www.canadianfootballresearch.ca. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ "The Football Team that History Forgot: 1941 Edmonton Eskimos - Canadi…". Archive.today. February 2, 2018. Archived from the original on February 2, 2018. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ a b c Oliver, Greg (October 16, 2003). "Stu Hart, the wrestler, circa 1946". Slam! Wrestling. Canadian Online Explorer. Archived from the original on August 18, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- ^ Mouallem, Omar (April 9, 2014). "Al Oeming: Nature lover and wrestler was larger than life". theglobeandmail.com. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ a b Will, Gary. "Stu Hart". Canadian Pro Wrestling Page of Fame. Archived from the original on February 20, 2009. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ "The News Journal from Wilmington, Delaware on August 2, 1946 · Page 12". Newspapers.com. August 2, 1946.

- ^ Staff (December 7, 1947). "Pro Wrestling". Sports; Wrestling. San Antonio Light. p. 41. Retrieved December 19, 2017 – via NewspaperARCHIVE.

- ^ Staff (December 15, 1949). "TO SEE HOUGH MATCHES". Sports; Wrestling. The Herald from Billings. p. 4. Retrieved December 19, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Winona Republican-Herald from Winona, Minnesota on November 10, 1950 · Page 13". Newspapers.com. November 10, 1950. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ Staff (April 6, 1949). "Stu Hart Drawing The Ladies To Rassle Shows". Sports; Wrestling. Independent Record. p. 7. Retrieved April 9, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Staff (September 28, 1949). "Wrestling Will Open With Bang At Armory Arena Friday Night When Six Muscle Men Meet". Sports; Wrestling. Independent Record. p. 9. Retrieved April 9, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Staff (December 16, 1951). "Gagne Hart to Headline Monday Wrestling Show". Sports; Wrestling. La Crosse Tribune. p. 22. Retrieved December 19, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Staff (December 17, 1951). "Gagne, Hart Top Mat Card". Sports; Wrestling. La Crosse Tribune. p. 11. Retrieved April 9, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Stampede Wrestling gets pinned". CBC Television News. January 10, 1990. Archived from the original on April 20, 2004.

- ^ Hart, Bret (April 17, 2004). "Positive heroes key for kids". SLAM! Wrestling. Canadian Online Explorer. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- ^ "Hart of a Tiger". SLAM! Wrestling. Calgary Sun. Archived from the original on January 9, 2016. Retrieved February 11, 2016 – via Canadian Online Explorer, aka Canoe.com.

- ^ Mihaly, John (October 2009). "Hart Exhibition". WWE Magazine. p. 3. Retrieved May 13, 2016 – via InfiniteCore.ca.

- ^ Stampede Wrestling - July 25, 1986 at WrestlingData.com

- ^ Hoops, Brian (May 26, 2008). "Nostalgia Review: WCW Slamboree 1993; Vader vs. Davey Boy Smith; Hollywood Blonds vs. Dos Hombres; Nick Bockwinkel vs. Dory Funk Jr". THE SPECIALISTS. Pro Wrestling Torch. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- ^ "Slamboree 1993". ProWrestlingHistory.com. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- ^ "Five Questions with… Jushin Thunder Liger". Si.com. July 13, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ "Billy Graham profile". Online World of Wrestling.

- ^ "Wrestler Bret Hart's childhood memories". CBC. December 12, 2007.

- ^ a b Wood, Greg (November 7, 1999). "The sadist, the loving father and a knockout end". The Independent. Archived from the original on May 25, 2022. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ "Bret Hart autobiography - My Real Life in the Cartoon World of Wrestling". Prowrestling.net. December 11, 2008.

- ^ "WebCite query result". www.webcitation.org. Archived from the original on May 4, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ^ "Ben Bassarab profile". cagematch.net. CAGEMATCH - The Internet Wrestling Database. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ F4W staff (July 23, 2015). "Dan Spivey, Billy Jack Haynes and Bryan Clarke Have Been Going Back-and-Forth on Social Media". F4wonline.com. Wrestling Observer Newsletter.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e "Stu Hart Profile". Online World of Wrestling. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- ^ "Exclusive interview: Bret Hart separates fact from fiction on who really trained in Stu Hart's Dungeon". Wwe.com. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ Lunney, Doug (January 15, 2000). "Benoit inspired by the Dynamite Kid, Crippler adopts idol's high-risk style". SLAM! Wrestling. Winnipeg Sun. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved February 14, 2017 – via Canadian Online Explorer.

- ^ Haldar, Prityush (October 2, 2016). "Chris Jericho talks about learning from Stu Hart", Sportskeeda; retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Stu Hart". Photos and Bios. Professional Wrestling Online Museum. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ^ Smith, Caleb (April 30, 2014). "Tyler Mane's movie career all started with wrestling". SLAM! Wrestling. Canadian Online Explorer. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- ^ Clevett, Jason (November 3, 2004). "The legend of Jushin "Thunder" Liger". Canadian Online Explorer. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- ^ "Nikolai Volkoff WWE Hall of Fame Profile", WWE.com; retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ "Ricky Fuji Puroresu Central profile", PuroresuCentral.com; retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ^ Hotton, Troy. "Inlewd Book Review: Under The Mat: Inside Wrestling's Greatest Family". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ Oliver, Greg (January 30, 2016). "The Hart Family". Canoe.com. Archived from the original on August 22, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ^ Back To The Territories #03 | Lance Storm Calgary, retrieved April 5, 2022

- ^ Hart, Bret (April 30, 2003). "Stu Hart, my dad, My Hero". Slam! Wrestling. Canadian Online Explorer. Archived from the original on April 10, 2016. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ^ Sands, David (April 18, 2001). "Klein sends best wishes to Stu Hart". Slam! Wrestling. Canadian Online Explorer. Archived from the original on August 18, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ Bell, Rick (June 1, 2001). "Nation salutes legendary Stu". Calgary Sun. Archived from the original on August 18, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2015 – via Canoe.com.

- ^ Maxwell, Cameron (April 28, 2001). "Hart may need pacemaker surgery". Slam! Wrestling. Canadian Online Explorer. Archived from the original on August 18, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2015 – via Canoe.com.

- ^ Norton, Blake (April 27, 2001). "Stu Hart to undergo surgery". Slam! Wrestling. Canadian Online Explorer. Archived from the original on August 18, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2015 – via Canoe.com.

- ^ "Hart-felt wishes inspire Stu". Slam! Wrestling. Calgary Sun. April 23, 2001. Archived from the original on August 18, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2015 – via Canadian Online Explorer at Canoe.com.

- ^ BILL KAUFMANN and JIM WELLS (October 17, 2003). "King of Harts dead". Slam! Wrestling. Calgary Sun. Archived from the original on August 18, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2015 – via Canadian Online Explorer at Canoe.com.

- ^ Kaufmann, Bill (October 24, 2003). "Honouring Stu". Calgary Sun. Archived from the original on August 18, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2015 – via Canadian Online Explorer at Canoe.com.

- ^ Clevett, Jason (October 24, 2003). "Friends and family celebrate Stu". SLAM! Wrestling. Canadian Online Explorer. Archived from the original on August 18, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ Morrison, Mike (2015). "5 Unexpected Finds at the Glenbow Museum". VisitCalgary.com. Explore Calgary. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ "Stu Hart". The Stories Behind the Stars. Professional Wrestling Online Museum. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ^ "Mavericks: Stu Hart". Glenbow.org. Glenbow Museum. Archived from the original on August 2, 2019. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ "Who Is Bret Hart? The Sports Legend's Controversial Career Changed Wrestling". Oxygen Official Site. April 17, 2019.

- ^ "StormWrestling.com - Commentary". www.stormwrestling.com. Archived from the original on January 28, 2018. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- ^ "StormWrestling.com - Commentary". Archive.today. January 28, 2018. Archived from the original on January 28, 2018. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ "CANOE -- SLAM! Sports - Wrestling - Honouring Stu". Archive.today. January 28, 2018. Archived from the original on January 28, 2018. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ BONNELL, Keith (March 27, 2010). "Bret Hart hits the ring at WrestleMania". The Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on March 31, 2010. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ Rhodes, Ted (December 4, 2015). "Hart family wrestlers to take to the ring in Hopes & Ropes charity match". Ottawa Citizen. Archived from the original on April 22, 2016.

- ^ Rhodes, Ted (December 5, 2015). "Wrestlers from Calgary's Hart family and Dungeon Discipline wrestling school are scheduled to take to the ring on Dec. 13 for the Hopes & Ropes charity match, put on by Hart Legacy". Edmonton Journal. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ Sarah O. Swenson (January 8, 2013). "Wetaskiwin wrestlers take part in prestigious meet". Wetaskiwintimes.com. Wetaskiwin Times-Advertiser. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- ^ "2014-2015-AAWA-Schedule" (PDF). Albertaamateurwrestling.ca. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ "Stu Hart Tournament of Champions (Calgary, Alberta)". Oawa.ca. Ontario Amateur Wrestling Association.

- ^ Staff (2003). "Stu Hart Tournament of Champions results". Saskwrestling.com. Saskatchewan Amateur Wrestling Association. Archived from the original on August 2, 2016. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ Price, Patrick (January 9, 2014). "Wrestlers show why they're the best in Japan". Cochranetimes.com. Cochrane Times. Archived from the original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ "Stu Hart Wrestling Tournament : Canadian High School Dual Meet : Championships Crescent Heights HS Calgary, Alberta" (PDF). Oawa.ca. January 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ "Sarnia Observer". Sarnia Observer. Archived from the original on January 8, 2018. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ "USA women win Stu Hart Cadet Duals in Canada". Teamusa.org. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ "USA women win Stu Hart Cadet Duals in Canada". Archive.today. January 15, 2018. Archived from the original on January 15, 2018. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ "TheMat.com - The Official Website of USA Wrestling". January 17, 2015. Archived from the original on January 17, 2015.

- ^ "Blairmore Suburban Centre" Archived April 13, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, City of Saskatoon website; accessed May 25, 2017.

- ^ "Surviving the Dungeon: The Legacy of Stu Hart". Online World Of Wrestling' retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ^ Elliott, Brian (November 4, 2009). "Surviving The Dungeon filmmaker's legacy as much as Stu Hart's". SLAM! Wrestling. Canadian Online Explorer. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ^ Elliott, Brian (November 23, 2009). "Hart Dungeon DVD gives rough picture of Stu". SLAM! Wrestling. Canadian Online Explorer. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ^ Powell, Jason (April 30, 2010). "Stu Hart documentary featuring interviews with Hart family members and WWE star David Hart Smith now available free online". prowrestling.net. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ^ Glazer, Pulse (May 10, 2010). "WWE Hall of Famer Stu Hart's Documentary 'Surviving the Dungeon'", insidepulse.com; retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ^ Johnson, Mike (April 30, 2010). "WWE Releasing 2010 First Quarter Results Next Week, WWE Back in HBK Country, Stu Hart Documentary Available and More", Pro Wrestling Insider; retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ^ "Welcome to The Wrestling Dungeon". April 24, 2016. Archived from the original on April 24, 2016.

- ^ "Wrestler shows real "Hart" | BramptonGuardian.com". August 23, 2018. Archived from the original on August 23, 2018.

- ^ Hunt, Stephen (September 11, 2005). "Hear from living mavericks" Archived May 31, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Calgary Herald; retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ^ "Maverick voices". Calgary Herald. March 24, 2007. Archived from the original on May 17, 2023. Retrieved July 20, 2023 – via PressReader.

- ^ "Stewart E. "Stu" Hart". Alberta Sports Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on September 2, 2024. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ "Inductee: Stu Hart". National Wrestling Hall of Fame. Retrieved May 27, 2017. https://archive.today/20180104172642/https://nwhof.org/blog/dg-inductees/stu-hart/

- ^ "List of CAC Award Winners - Cauliflower Alley Club". Caulifloweralleyclub.org. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ Klingman, Kyle (June 20, 2008). "Flood won't stop Tragos/Thesz HOF 'Super Weekend'". Slam! Wrestling. Canadian Online Explorer. Archived from the original on July 23, 2017. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- ^ "Northwest Tag Team Title (British Columbia)". Puroresu Dojo. 2003.

- ^ Pedicino, Joe; Solie, Gordon (hosts) (August 1, 1987). "Pro Wrestling This Week". Superstars of Wrestling. Atlanta, Georgia. Syndicated. WATL.

- ^ Caldwell, James (November 26, 2013). "News: Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame announces 2014 HOF class". Pro Wrestling Torch; retrieved November 26, 2013.

- ^ "Masks and laughs story of Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame induction". Slam.canoe.com. Archived from the original on August 22, 2016. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ "CANOE -- SLAM! Sports - Wrestling - Masks and laughs story of Pro Wre…". Archive.today. August 2, 2016. Archived from the original on August 2, 2016. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ Whalen, Ed (host) (December 15, 1995). "Stampede Wrestling Hall of Fame: 1948-1990". Showdown at the Corral: A Tribute to Stu Hart. Event occurs at 15:38. Shaw Cable. Calgary 7.

- ^ "Stampede Wrestling Hall of Fame (1948–1990)", Puroresu Dojo; retrieved November 26, 2013.

- ^ "Wrestling Observer Hall of Fame 1996 Inductees" Archived September 2, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, pwi-online.com; accessed May 25, 2017.

- ^ a b Oliver, Greg (April 3, 2016). "Canadian Wrestling Hall of Fame". SLAM! Wrestling. Canadian Online Explorer. Archived from the original on April 29, 2015 – via Canoe.com.

- ^ Clevette, Jason (June 16, 2010). "Booker T enjoying life away from the spotlight". SLAM! Wrestling. Canoe.com. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018. Retrieved January 16, 2018.

- ^ "CANOE -- SLAM! Sports - Wrestling - Championship calibre matches make PWA Supercard". July 23, 2017. Archived from the original on July 23, 2017.

- ^ "Hangman". Online World Of Wrestling; retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ Hart, Bret (February 24, 2001). "Stu deserves huge honour". Calgary Sun. Archived from the original on April 13, 2016. Retrieved May 25, 2017 – via Canadian Online Explorer.

- ^ Staff (2012). "100 Outstanding Albertans". Calgarystampede.com. Archived from the original on January 30, 2018. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ Staff (1999). "1999 CALGARY AWARD RECIPIENTS" (PDF). Calgary.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 31, 2018. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b McCoy 2007, p. 15.

- ^ a b c d Meltzer 2004, p. 96.

- ^ Toombs 2002, p. Foreword.

- ^ a b Berger 2010, p. 54.

- ^ a b van Herk 2002, p. ?.

- ^ a b c Erb 2002, p. 72.

- ^ a b Pope 2005, p. 218.

- ^ a b Waddell/Taras 2016, p. 296.

- ^ Lister 2005, p. 252.

- ^ McCoy 2007, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Hart, Martha 2004, p. 30.

- ^ Hart, Diana 2001, p. 11.

- ^ McCoy 2007, p. 19.

- ^ Erb 2002, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d Marshall 2016, p. 193.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mlazgar/Stoffel 2007, p. 58.

- ^ a b McCoy 2007, p. 24.

- ^ a b c Berger 2010, p. 57.

- ^ McCoy 2007, p. 25.

- ^ a b c d McCoy 2007, p. 26.

- ^ Lentz III 2015, p. 262.

- ^ a b c Keith 2008, p. 41.

- ^ Verrier 2017, p. 71.

- ^ McCoy 2007, p. 27.

- ^ McCoy 2007, p. 31.

- ^ Meltzer 2004, p. 100.

- ^ Grasso 2014, p. 131.

- ^ a b Sullivan 2011, p. 92.

- ^ Martin 2001, p. 68.

- ^ Solomon 2015, p. ?.

- ^ Toombs 2016, p. ?.

- ^ Hart, Bruce 2011, p. ??.

- ^ Pope 2005, p. 213.

- ^ Hart, Martha 2004, p. 20.

- ^ McCoy 2007, p. 236.

- ^ a b Hart, Bret 2007, p. 329.

- ^ Hart, Bret 2007, p. 334.

- ^ Backlund 2015, p. ?.

- ^ Hart, Bret 2007, p. 11.

- ^ Davies 2002, p. 15.

- ^ Johnson 2012, p. ?.

- ^ McCoy 2007, p. 53.

- ^ Thunderheart 2014, p. 14.

- ^ a b Klein 2012, p. 25.

- ^ a b Hart, Martha 2004, p. 29.

- ^ Snowden 2012, p. ?1.

- ^ Matysik 2005, p. 48.

- ^ Erb 2002, p. 136.

- ^ Graham 2007, p. ?.

- ^ Kerekes 1994, p. 18–20.

- ^ Muchnick 2009, p. ?1.

- ^ Jericho 2008, p. ?1.

- ^ Randazzo 2008, p. 47.

- ^ Erb 2002, p. 137.

- ^ Hart, Martha 2004, p. 31.

- ^ a b Davies 2002, p. 19.

- ^ Hornbaker/Snuka 2012, p. ??1.

- ^ Hart, Jimmy 2004, p. 124.

- ^ Hart, Bret 2000.

- ^ Toombs 2016, p. ??.

- ^ Hornbaker/Snuka 2012, p. ???1.

- ^ Verrier 2017, p. 106.

- ^ Martin 2001, p. 69.

- ^ Hornbaker/Snuka 2012, p. ????1.

- ^ Zawadzki 2001, p. 175.

- ^ McCoy 2007, p. 66.

- ^ Hornbaker 2007, p. 252.

- ^ a b Conacher 2013, p. 173.

- ^ Hart, Diana 2001, p. 1.

- ^ Hart, Bret 2007, p. 531.

- ^ Hart, Bret 2007, p. 169.

- ^ Wall 2012, p. 276.

- ^ Byfield 2002, p. 236.

- ^ McCoy 2007, p. 37.

- ^ a b WON 2003, p. 1.

- ^ McCoy 2007, p. 272.

- ^ Hart, Bruce 2011, p. ?.

- ^ Hart, Bret 2007, p. 541.

- ^ Hart, Bret 2007, p. 545.

- ^ Randazzo 2008, p. 30.

- ^ Hornbaker/Snuka 2012, p. ?1.

- ^ Keith 2008, p. 26.

- ^ Meltzer 2004, p. 10.

- ^ Meltzer 2004, p. 98.

- ^ Matysik 2013, p. ?1.

- ^ WON 2004, p. 83.

- ^ Meltzer 2004, p. 97.

- ^ McCoy 2007, p. 23.

- ^ "2021 Class". Canadian Pro-Wrestling Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on January 27, 2023. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ^ Hart, Bret 2007, p. 333.

- ^ Hart, Bret 2007, p. 326.

Bibliography

[edit]- Erb, Marsha (2002). Stu Hart: Lord of The Ring ー An Inside Look at Wrestling's First Family. ECW Press. ISBN 1-55022-508-1 – via Google Books.

- Bob Backlund (2015). The All-American Kid: Lessons and Stories on Life from Wrestling Legend Bob Backlund. Sports Publishing. ISBN 978-1613216958 – via Google Books.a

- Hart, Bret (2007). Hitman: My Real Life in the Cartoon World of Wrestling. Random House Canada (Canada), Grand Central Publishing (US). 592pp. ISBN 9780307355676 – via Google Books. ISBN 978-0-307-35567-6 (Canada) ISBN 978-0-446-53972-2 (US)

- Hart, Bret; Lefko, Perry (March 2000). Bret "Hitman" Hart: The Best There Is, the Best There Was, the Best There Ever Will Be. Balmur/Stoddart Publishing. ISBN 0-7737-6095-4 – via Internet Archive.

- Davies, Ross (2002). Bret Hart. (Wrestling Greats). Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0823934942 – via Google Books.

- Conacher, Brian (2013). As the Puck Turns: A Personal Journey Through the World of Hockey. HarperCollins. p. 304. ISBN 9781443429597 – via Google Books.

- Greg Klein (2012). The King of New Orleans: How the Junkyard Dog Became Professional Wrestling's First Black Superhero. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1770410305 – via Google Books.

- Chris Jericho (2008). A Lion's Tale: Around the World in Spandex. Orion. ISBN 978-0752884462 – via Google Books.

- Hart, Diana; McLellan, Kirstie (2001). Under the Mat: Inside Wrestling's Greatest Family. Fenn. ISBN 1-55168-256-7.b

- Hart, Bruce (2011). Straight from the Hart. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1-55022-939-4 – via Google Books.a

- Hart, Jimmy (2004). The Mouth of the South: The Jimmy Hart Story. Ebury Press. ISBN 978-1550225952 – via Google Books.

- Billy Graham (2007). WWE Legends – Superstar Billy Graham: Tangled Ropes. Gallery Books. ISBN 978-1416524403 – via Google Books.a

- Hart, Martha; Francis, Eric (2004). Broken Harts: The Life and Death of Owen Hart. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-59077-036-8 – via Google Books.

- Larry Matysik (2005). Wrestling at the Chase: The Inside Story of Sam Muchnick and the Legends of Professional Wrestling. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1550226843 – via Google Books.

- Marshall, Andy (2016). Thin Power: How former Calgary Mayor Rod Sykes stamped his brand on the city . . . And scorched some sacred cows. FriesenPress. ISBN 9781460283967 – via Google Books.a

- Toombs, Roderick; Picarello, Robert (2002). In the Pit With Piper. Berkley Publishing. ISBN 978-0-425-18721-0 – via Google Books.

- Ariel Teal Toombs; Colt Baird Toombs (2016). Rowdy: The Roddy Piper Story. Random House of Canada. ISBN 978-0-345-81623-8 – via Google Books.a

- Berger, Richard (2010). A Fool for Old School ... Wrestling, That is. Richard Berger & Barking Spider Productions. ISBN 978-0981249803 – via Google Books.

- Verrier, Steven (2017). Professional Wrestling in the Pacific Northwest: A History, 1883 to the Present. McFarland Publishing. ISBN 978-1476670027 – via Google Books.

- Hornbaker, T.; Snuka, J. (2012). Legends of Pro Wrestling: 150 Years of Headlocks, Body Slams, and Piledrivers. Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 9781613213148 – via Google Books.

- Martin, James (2001). Calgary: The Unknown City. Arsenal Pulp Press. ISBN 978-1551521114 – via Google Books.

- Byfield, Ted (2002). Alberta in the 20th century: The sixties revolution & the fall of Social Credit. United Western Communications. ASIN B00A96P3R0 – via Google Books.

- Wall, Karen L. (2012). Game Plan: A Social History of Sports in Alberta. University of Alberta Press. ISBN 978-0888645944 – via Google Books.

- Hornbaker, Tim (2007). National Wrestling Alliance: The Untold Story of the Monopoly That Strangled Pro Wrestling. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1550227413 – via Google Books.

- Sullivan, Kevin (2011). The WWE Championship: A Look Back at the Rich History of the WWE Championship. World Wrestling Entertainment. ISBN 978-1439193211 – via Google Books.

- McCoy, Heath (2007). Pain and Passion: The History of Stampede Wrestling - Revised Edition (Second ed.). ECW Press. ISBN 978-1-55022-787-1 – via Google Books.

- McCoy, Heath (2005). Pain and Passion: The History of Stampede Wrestling (First ed.). CanWest. ISBN 978-1-55022-787-1 – via Google Books.c

- van Herk, Aritha (2002). Mavericks: An Incorrigable History Of Alberta. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140286021 – via Google Books.a

- Matysik, Larry (2013). 50 Greatest Professional Wrestlers of All Time: The Definitive Shoot. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1770411043 – via Google Books.

- Grasso, John (March 6, 2014). Historical Dictionary of Wrestling. Scarecrow Press, inc. ISBN 978-0-8108-7926-3 – via Google Books.

- Zawadzki, Edward (2001). The Ultimate Canadian Sports Trivia Book. Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-0-88882-237-6 – via Google Books.

- Matthew Randazzo V (2008). Ring of Hell: The Story of Chris Benoit & the Fall of the Pro Wrestling Industry. Phoenix Books. ISBN 978-1597775793 – via Google Books.

- Irvin Muchnick (2009). Chris and Nancy: The True Story of the Benoit Murder-Suicide and Pro Wrestling's Cocktail Of Death. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1550229028 – via Google Books.

- Keith, Scott (2008). Dungeon of Death: Chris Benoit and the Hart Family Curse. Citadel Press. ISBN 978-0806530680 – via Google Books.

- David Kerekes (1994). Headpress: Journal of Sex, Religion, Death, magazine #9. Headpress – via Google Books.

- Jonathan Snowden (2012). Shooters: The Toughest Men in Professional Wrestling. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1770410404 – via Google Books.

- Meltzer, Dave. Wrestling Observer Newsletter. Wrestling Observer.

- Meltzer, Dave (2003). Wrestling Observer Newsletter, 2003. Wrestling Observer – via Google Books.

- Meltzer, Dave (2004). Wrestling Observer Newsletter, 2004. Wrestling Observer – via Google Books.

- Rodd Thunderheart (2014). See Through Love. FriesenPress. ISBN 978-1460238752 – via Google Books.

- Steven Johnson; Greg Oliver (2012). The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: Heroes and Icons. J J Dillion (foreword), Mike Mooneyham (contributor). Ebury Press. ISBN 978-1770410374 – via Google Books.a

- Meltzer, Dave (2004). Tributes II: Remembering More of the World's Greatest Professional Wrestlers. Sports Publishing. ISBN 1-58261-817-8 – via Internet Archive.

- Mlazgar, Brian; Stoffel, Holden (2007). Saskatchewan Sports: Lives Past and Present. University of Regina Press. ISBN 978-0889771673 – via Google Books.

- Pope, Kristian (2005). Tuff Stuff Professional Wrestling Field Guide: Legend and Lore. Krause Publishing. ISBN 978-0896892675 – via Google Books.[permanent dead link]

- Lister, John (November 3, 2005). Slamthology: Collected Wrestling Writings 1991-2004. Lulu.com. ISBN 1-4116-5329-7 – via Google Books.

- Lentz III, Harris M. (2015). Obituaries in the Performing Arts, 2014. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786476664 – via Google Books.

- Waddell, Christopher; Taras, David (2016). How Canadians Communicate V: Sports. Athabasca University Press. ISBN 978-1771990073 – via Google Books.

- Solomon, Brian (2015). Pro Wrestling FAQ: All Thats Left to Know About the Worlds Most Entertaining Spectacle. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1617135996 – via Google Books.a

Annotations

[edit]- ^ Some, or all versions of this book may lack page numbering.

- ^ Diana Hart's book has been criticized as a highly biased work.

- ^ The 2005 edition does not include the chapters "Harts Go On" and "2007: The Third Generation and Wrestling's Darkest Day".

Sources

[edit]|

Film |

|

Web

|

|

Further reading

[edit]Books

[edit]- Hart, Julie (2013). Hart Strings. Tightrope Books. ISBN 978-1926639635.

- Billington, Tom; Coleman, Alison (2001). Pure Dynamite: The Price You Pay for Wrestling Stardom. Winding Stair Press. ISBN 1-55366-084-6.

Articles

[edit]- art, Bret (May 6, 2000), "Heart of gold lies beneath gruff exterior", Calgary Sun, archived from the original on April 13, 2016 – via Canoe.com

- Clevett, Jason (March 9, 2005), "Walk of Fame shuns Stu Hart: Famous patriarch not chosen for 2005 despite campaign", SLAM! Wrestling, Canadian Online Explorer, archived from the original on August 18, 2015

- Canadian wrestling patriarch Stu Hart dies[usurped] – By Judy Monchuk – The Canadian Press

- Montoro, Angel G. (September 18, 2009), "Stu Hart : Una leyenda canadiense", SoloWrestling (in Spanish), archived from the original on April 10, 2018

- The Lethbridge Herald from Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada on January 10, 1953 · Page 7

- The Morning News from Wilmington, Delaware on April 9, 1947 · 17

- Poughkeepsie Journal from Poughkeepsie, New York on April 20, 1947 · Page 14

External links

[edit]- Stu Hart's profile at Cagematch.net , Wrestlingdata.com , Internet Wrestling Database

- Stu Hart at IMDb

- Stu Hart at Find a Grave

- WWE Hall of Fame profile at WWE.com

- Order of Canada: Stewart Edward Hart, C.M., at archive.gg.ca by Governor General of Canada

- Stu Hart

- 1915 births

- 2003 deaths

- Canadian military personnel from Saskatchewan

- Alberta Sports Hall of Fame inductees

- Canadian male professional wrestlers

- Canadian catch wrestlers

- Deaths from diabetes in Canada

- Edmonton Elks players

- Members of the Order of Canada

- Players of Canadian football from Alberta

- Players of Canadian football from Saskatchewan

- Professional wrestlers from Saskatchewan

- Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame and Museum

- Professional wrestling trainers

- Sportspeople from Saskatoon

- Stampede Wrestling alumni

- WWE Hall of Fame inductees

- Canadian people of English descent

- Canadian people of Ulster-Scottish descent

- Hart wrestling family members

- Professional wrestling promoters

- Professional wrestling managers and valets

- Royal Canadian Navy personnel of World War II

- 20th-century male professional wrestlers

- 20th-century Canadian professional wrestlers

- 20th-century Canadian sportsmen